Prepared by:

N. Shilpa, Assistant Professor

Department of ECE, SR University, Warangal, Telangana – 506371

Introduction

India, a nation built on rich cultural traditions and a rapidly expanding economy, continues to grapple with a deeply rooted challenge—gender imbalance at birth. Persistent son preference driven by socio-cultural norms has led to a declining birth rate of girls, with far-reaching implications for the nation’s social fabric and economic future. Despite legislative efforts and awareness programs, the skewed sex ratio at birth underscores the enduring nature of gender bias and systemic inequality.

1. The Girl Child Birth Rate: A Statistical Snapshot

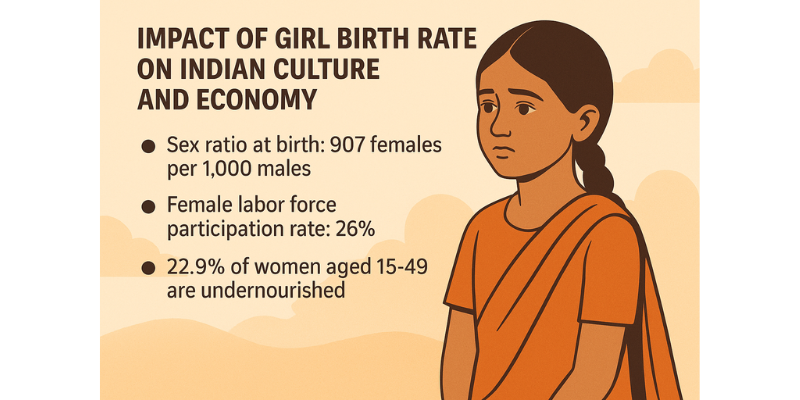

According to the Sample Registration System (SRS) Statistical Report 2020 by the Registrar General of India, the Sex Ratio at Birth (SRB) stands at 907 girls per 1,000 boys, well below the natural norm of 952–980. This deficit is a clear indication of sex-selective practices and discrimination against female children.

States with the most skewed SRB include:

-

Uttarakhand – 844

-

Haryana – 870

-

Punjab – 890

-

Delhi – 899

This reflects a widespread cultural preference for sons, leading to female foeticide, infanticide, and even abandonment of girl children.

2. Cultural Impact of a Low Girl Birth Rate

A. Social Disequilibrium and Marital Crisis

A declining number of women leads to marriage imbalances, particularly in northern states like Haryana and Punjab. According to a 2019 study published in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, the shortage has led to the trafficking and coercion of women from other states to serve as brides, resulting in forced marriages, abuse, and exploitation.

B. Reinforcement of Gender Stereotypes

A lower birth rate of girls reinforces the perception of daughters as liabilities, strengthening practices such as dowry, child marriage, and educational neglect. The underrepresentation of women in public life, leadership, and policymaking further hampers social inclusivity and diversity.

3. Economic Implications of a Low Girl Birth Rate

A. Shrinking Future Workforce

India’s demographic advantage can only be realized if both genders have equal access to education and employment. However, with only 26% female labor force participation (World Bank, 2023), the gender imbalance limits the country’s economic potential and diminishes the quality of its human capital.

B. Increased Health and Welfare Burden

Neglect of the girl child—through poor nutrition, education, and healthcare access—results in a cycle of poverty and dependency. According to NFHS-5 (2019–21), 22.9% of Indian women aged 15–49 are undernourished, which contributes to high maternal and infant mortality rates.

In response, the government runs various schemes such as:

-

Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao (BBBP)

-

Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana

-

Kanya Sumangala Yojana

These programs aim to uplift the status of girls but also highlight the long-term cost of systemic gender bias.

C. Impact on Economic Equity

Fewer girls today mean fewer female entrepreneurs, leaders, and innovators tomorrow. India ranks 127th out of 146 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2024, signaling the economic consequences of unequal gender participation. Nations with greater gender parity are more resilient, equitable, and prosperous.

4. Root Causes of Gender Discrimination at Birth

-

Patriarchal Values: Sons are seen as family heirs and economic protectors.

-

Dowry System: Daughters are considered financial burdens.

-

Lack of Social Security: Sons are viewed as support in old age.

-

Religious Beliefs: Sons are traditionally required to perform last rites.

Addressing these entrenched beliefs requires multi-pronged intervention across policy, education, media, and community platforms.

5. Government Reforms and Initiatives

India has implemented key measures to tackle gender discrimination:

-

Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994: Bans sex-selective abortions.

-

Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao Scheme (2015): Aims at survival, protection, and education of the girl child.

-

Conditional Cash Transfer Programs: Offer financial incentives to families raising daughters.

However, implementation gaps remain. A 2019 CAG audit revealed that over 70% of BBBP funds were spent on publicity, with minimal grassroots impact.

6. Pathway to Sustainable Change: Building Positive Attitudes

True change requires social transformation beyond legal mandates:

-

Community-driven awareness campaigns to celebrate daughters.

-

Empowerment through education, skills, and entrepreneurship.

-

Progressive media representation breaking gender norms.

-

Engaging men and boys in the fight for equality.

States like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Himachal Pradesh demonstrate that positive change is possible through inclusive governance and active citizen participation.

Conclusion

The declining birth rate of girls is not just a gender issue—it is a threat to India’s cultural integrity, human rights, and economic development. As India aspires to global leadership, it cannot afford to marginalize half its population. Every girl has the potential to be a change-maker—a teacher, doctor, entrepreneur, or leader.

Promoting gender equality from birth is not just a moral imperative; it is a national necessity. A balanced, inclusive, and equitable future for India begins with valuing every girl child.